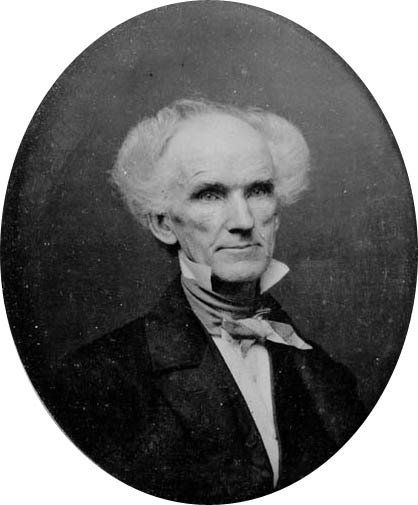

Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint: James B. Longacre

Fourth Chief Engraver of the United States Mint

The Fourth Chief Engraver of the United States Mint.

We’ve covered the previous Chief Engravers, and if you’d like to check out those articles you can find them here!

- Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint: Robert Scot

- Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint: William Kneass

- Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint: Christian Gobrecht

James B. Longacre’s time at the U.S. Mint was quite an eventful one, in fact Longacre’s entire life had some pretty interesting things going on. From running away from home as a boy to dealing with internal politics and sabotage at the Mint. If that sounds like something you want to hear about, then you’re in the right place!

A Young Artist’s Talent Emerges

James’ life began on a small farm in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, on August 11, 1794. He was born to Peter Longacre and Sarah (Barton) Longacre. Tragedy struck only a few years later when his mother passed away.

James’ father Peter eventually remarried, and this didn’t sit well with James. He felt this new life without his mother, and with his father’s new wife was intolerable, and at the age of 12 he ran away from home. He headed to Philadelphia and began an apprenticeship at a bookstore.

The owner of the bookstore, John E. Watson, took James into his own family in addition to apprenticing him for a few years. Over those years, Watson began to realize that James’ real talent was in portraiture. In 1813, Watson released him from the apprenticeship, to allow him to pursue his artistic endeavors. They remained close, and Watson often sold James’ work in his shop.

James B. Longacre then began an apprenticeship with George Murray at Murray, Draper, Fairman and Co. the same firm his predecessor, as Chief Engraver, Christian Gobrecht, would join in 1816. During his time at the firm, Longacre’s most important works were portraits of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Hancock, which were used on a facsimile of the Declaration of Independence by publisher John Binns.

A Long Career As An Engraver Begins

Longacre remained at the firm until 1819, when he left and set up his own shop, using the reputation, skill, and knowledge he gained while at the firm. He had become quite recognized as a skilled engraver with the talent for rendering other artist’s paintings into printed engravings.

His business was doing well, and the first important commissions he had were plates for S.F. Bradford’s in 1820, and an engraving of Andrew Jackson, based on a portrait by Thomas Sully. These were both very successful works and gained him much recognition.

Longacre then entered into a contract to engrave illustrations for Joseph and John Sanderson’s Biographies of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, which was published in 9 volumes between 1820 and 1827.

The book received some criticism in regards to the writing, but the sales were good enough that the project was completed. Numismatic writer Richard Snow speculated that the book sold solely on the strength of the quality of Longacre’s illustrations.

After completing the Sanderson series, Longacre decided to create his own set of biographies illustrated with plates of the subjects. He was on the verge of launching the project, when he learned that James Herring of New York City had been planning a similar series.

Longacre wrote to Herring, and they decided to collaborate on the project together. It was titled The American Portrait Gallery but later changed to the National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans (Whew! That’s a long one!).

Longacre gained even more popularity and renown for his engraving work, South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun was especially taken with him and his work, which would later help him achieve the position of Chief Engraver. In 1832, Niles’ Register (a “magazine” at the time) described a Longacre engraving as “one of the finest specimens of American advancement in art”.

The Panic of 1837, And The Aftermath

As far as home life for James B. Longacre goes, in 1827 he married Miss Eliza Stiles, and the two had 5 children together. 10 years later panic hit, specifically the panic of 1837. With the financial crisis hitting the U.S. hard, Longacre was not spared from this and had to declare bankruptcy. Forced to travel the southern states going town to town and peddling his books. Fortunately later in that same year he was able to return home and open a banknote engraving firm; Toppan, Draper, Longacre and Co.

There was large demand for engraving, as there were new notes being issued from the banks, and as a result the firm prospered. They did so well in fact, they were able to open a second branch of their firm. According to Richard Snow (author of A Guide Book of Flying Eagle and Indian Head Cents) Longacre became known as the best engraver in the country.

In 1844, the current Chief Engraver, Christian Gobrecht, passed away and the Mint was in need of a new Chief Engraver. There were a couple other men in the running, but through his connections with senator John C. Calhoun, Longacre was able to secure the position.

Into The Lion’s Den

On September 16, 1844 James Barton Longacre was appointed Chief Engraver of the United States Mint. But it wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows from this point. According to Q. David Bowers, Longacre had “found that he had entered a hornet’s nest of intrigue, politics, and infighting, dominated by Franklin Peale, Chief Coiner since 1839”.

Longacre clashed spectacularly with Peale and Mint director Robert M. Patterson.

Peale would often have Mint employees work at his own private residence, he took advantage of his predecessor, who continued to work without pay, despite being retired. Peale also had a thriving side-hustle preparing dies for private medals, which would be fine, but he was using government resources to do all this.

Peale controlled all access to the dies and materials in the Mint and this made things difficult for Longacre to do any work. Peale and Patterson were close, and it turned out they were colluding and skimming metal from bullion deposits!

Longacre was a bit of an outcast in the Mint, nearly all the other employees were in the pocket of either Patterson or Peale so he was almost definitely shunned. During these first years though, Longacre honed his craft. He spent time learning all the processes he hadn’t learned when he was engraving solely portraits. He learned coin design, die sinking, and making punches for design elements.

During Longacre’s time at the Mint, Peale and his staff would often make punches without consulting Longacre (whose responsibility it was to oversee the punches) resulting in poorly made or incorrect punches. This was likely Peale attempting to sabotage Longacre’s work.

Despite everything, Longacre seemingly avoided conflict with Patterson and Peale until March of 1849, which was when Congress authorized a gold dollar, and a double eagle.

The Conflicts Begin

By that point, Patterson wanted Longacre out of the picture, as he was a direct threat to Peale’s medal side-business. Because of this, Patterson was openly opposed to anything which required the Chief Engraver’s skill. (Such as the new coins authorized by congress)

The issue arose when Longacre complained that Peale was monopolizing the Contamin Portrait Lathe--a machine needed for making the dies, but also used by Peale in his personal business--Peale retaliated by deciding to start sabotaging Longacre’s work to get him removed from his position as Chief Engraver.

Around this time, Longacre got a tip from one of the other Mint staff members that Peale was looking to get all the engraving work done from outside the Mint, which would make Longacre’s position obsolete.

Longacre’s response to this was to double-down and work as hard as possible on the new coins.

Here’s an account from Longacre about some of the difficulties of working with Peale and Patterson:

“The plan of operation selected for me was to have an electrotype mould made from my model, in copper, to serve as a pattern for a cast in iron.” --This was an unusual process that wasn’t normally used at the Mint--“The operations of the galvanic battery for this purpose were conducted in the apartments of the Chief Coiner. The galvanic process failed, my model was destroyed in the operation. I had, however, taken the precaution to make a cast in plaster… From this cast, as the only alternative, I procured a metallic one which, however, was not perfect, but I thought I should be able to correct the imperfections in the engraving of the die… This was a laborious task, but seasonably completed, entirely by my own hand. The die then had to be hardened in the coining department, it unluckily split in the process.”

There sure seemed to be a whole lot of bad “luck” whenever Longacre’s work entered Peale’s department!

When he was finally able to complete the double eagle, Peale immediately rejected them. Peale complained that the design was engraved too deep and wouldn’t fully strike without multiple strikes, and that there was no way it would stack properly.

Longacre Remained Steadfast

Peale took it even further and complained to Patterson. Patterson decided to write to Treasury Secretary William M. Meredith demanding Longacre be fired. Of course, Longacre objected to this by letter, stating that Peale was purposely delaying the acceptance of the updated double eagle design. Patterson responded by meeting with Longacre to tell him he was about to be fired and he should just resign now.

But Longacre didn’t resign

He got himself to Washington on Feb 12, 1850, and met with Meredith. It turned out that Peale and Patterson had been lying to Meredith about quite a few things. When Longacre showed him the test strike of the double eagle, Meredith was surprised, he had been told that the double eagles had completely failed and none had worked out.

Needless to say, the double eagle went into production by March of 1850, and Longacre stayed on at the Mint. Patterson did his fair share of complaining about the coins and about Longacre, but the coins did incredibly well.

The double eagle very quickly became the preferred way to hold gold. In the coming years, more gold would be struck into double eagles than into all other denominations combined! (Source Bowers, Q. David. The Harry W. Bass Jr. Museum Sylloge)

The Final Conflict

Patterson tried one more time to get James B. Longacre fired from the U.S. Mint, this time he alleged that President Zachary Taylor had decided Longacre should be dismissed. Despite this and all other attempts, Longacre remained in his position as Chief Engraver.

There was one final conflict in the Mint in 1851. Congress had authorized a three-cent silver piece. Initially Longacre’s design was approved by Patterson (surprisingly), but Peale wiggled his way in and persuaded Patterson to change his mind and instead authorize the Chief Coiner (Peale) to submit a design.

Both coins were submitted to the new Treasury Secretary, Thomas Corwin, who ended up selecting Longacre’s design. Longacre had taken the precaution of sending Corwin his coin separately, and explaining the imagery and design, as well as probably the conflicts going on in the Mint.

All inside conflict in the Mint finally came to a close when in July of 1851, Patterson retired as director of the U.S. Mint. Then, a year later, Adam Eckfeldt (The retired Chief Coiner), who was still doing all the duties of Chief Coiner passed away. This definitely threw a wrench in Peale’s side-hustle medal business!

A few years later, word leaked out of what Peale had been doing, and how he had been using Mint labor for private gain. Not to mention extremely taking advantage of Adam Eckfeldt, who kept working without pay!

New Mint Director James R. Snowden fired Peale after the information went public.

James B. Longacre continued on at the Mint as Chief Engraver, with life much improved since Patterson and Peale were gone. He remained until 1869, when he died suddenly at his home on New Years day.

There’s quite a bit to James Longacre’s story that I left out. We might revisit this with part two in the future so keep an eye out!

Check out some of our other articles in our Chief Engravers of the US Mint Series!

- Robert Scot

- William Kneass

- Christian Gobrecht

- James B. Longacre

- William Barber

- Charles E. Barber

- George T. Morgan

- John R. Sinnock