Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint: Charles Barber

Sixth Chief Engraver of the United States Mint

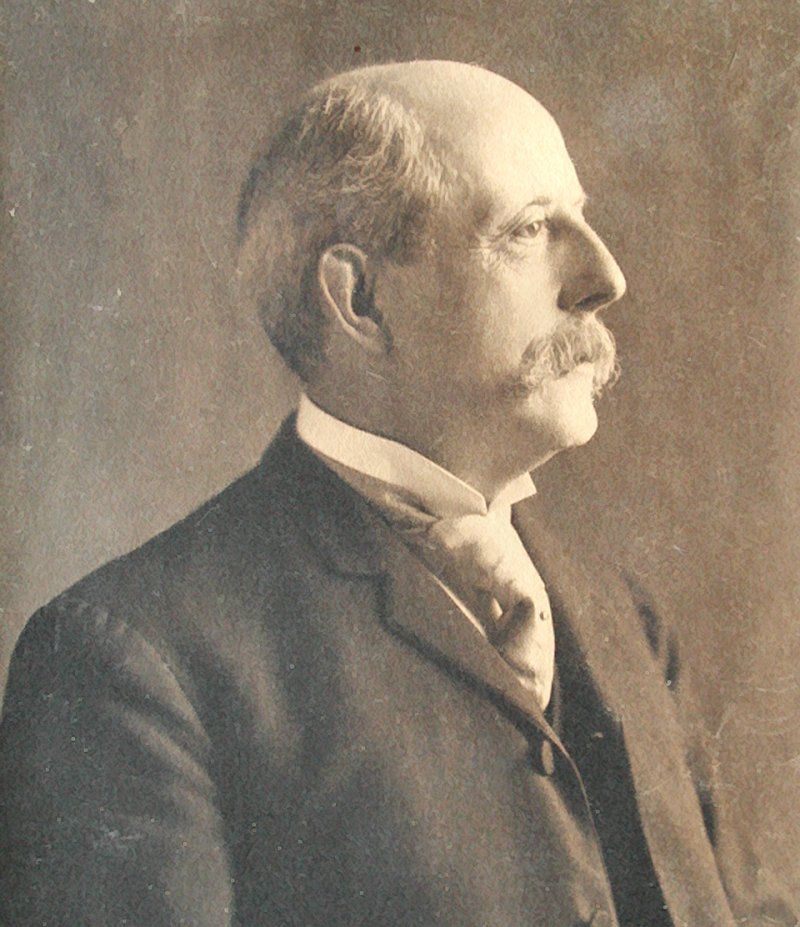

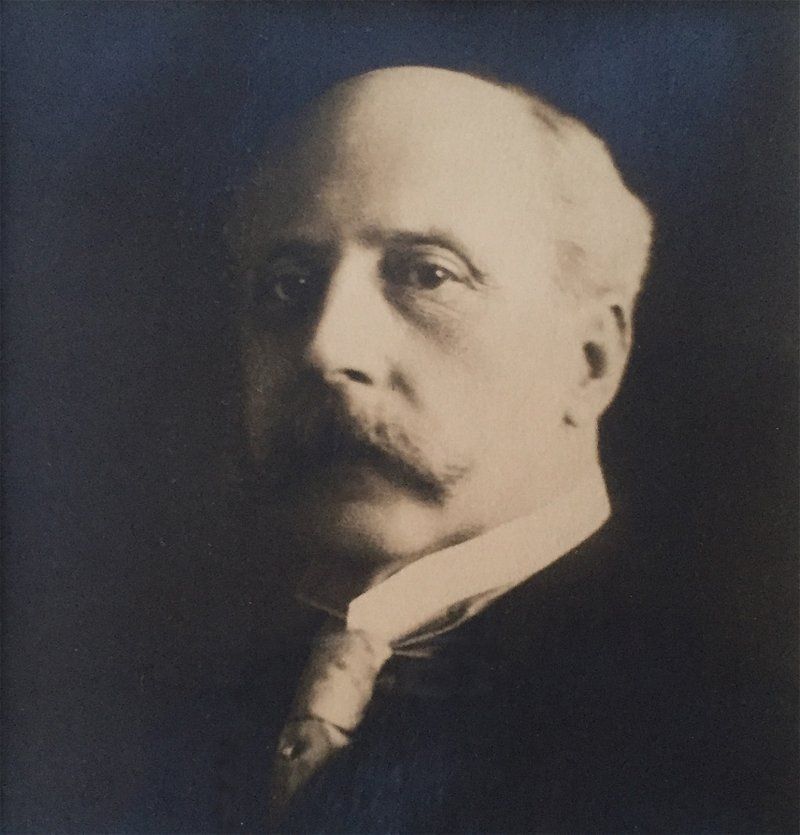

Continuing in our Chief Engraver series, we have William Barber’s son Charles E. Barber, following in his father’s footsteps as Chief Engraver.

Most likely you’ve heard some things about Charles Barber, namely that he was notoriously hard to work with, and did not have the best of relationships with either George T. Morgan, or the President--Theodore Roosevelt.

Supposedly this is not true, and couldn’t have been considering Morgan and Barber worked with each other for over 40 years! Now I wouldn’t say that means he’s a saint. I think he was just a stickler. A stickler for tradition and making sure things were exactly perfect.

We probably all know somebody like that right?

Beginning of a long career engraving coins

Charles Barber was born November 16, 1840 to parents William and Anna May in London, England. He had a brother and two sisters. In 1852, the family emigrated to the United States and settled around Boston.

When Charles’ father William was hired as an assistant engraver to James B. Longacre in 1865, the family made another move to Philadelphia.

In 1869 Charles was hired as an assistant engraver by his father William, who had been appointed Chief Engraver the same year.

Charles was still new to engraving at this point, and this time was mainly spent learning the trade from his father, but as engraving had been almost a family tradition, Barber duly learned the techniques and processes to successfully make great coinage.

Charles married Martha E. Jones, and in 1875 they had a daughter who sadly died in infancy. In 1885 they had another daughter named Edith who survived, and preserved many family archives and artifacts.

Moving up the ranks of the U.S. Mint

In 1879 William Barber passed away and the Mint needed a new Chief Engraver. George T. Morgan and Charles Barber were both strong contenders for the position, and many argue that Morgan should have been appointed (He did get the position after Charles died later).

After much deliberation, Charles was finally appointed Chief Engraver of the United States Mint by president Rutherford B. Hayes on January 20, 1880.

Charles Barber is probably best known for his Liberty Head coinage, the Barber dime, quarter and half dollar, and the famous Liberty Head V nickels.

Charles also designed many pattern coins, one of them being the $4 Gold Stella, the first and last of its kind. This coin was meant for joining the Latin Monetary Union, which would essentially allow the coin to be used across the world. There were two types of the Stella made, the flowing hair (designed by Barber) and the coiled hair (designed by Morgan)

The proposal to join the Latin Monetary Union was ultimately rejected by Congress, but before it was rejected, hundreds of the coins were sold to Congressmen at-cost. All Stella’s are rare and valuable now, but the ones with the year 1880 are the most rare, with only 25 examples known today.

Designing one of the most valuable coins in existence today

The Shield nickel was having production issues, and Barber was instructed to create a replacement for it. In 1883, he produced the Liberty Head V nickel, which was his first mainstream coin.

The Liberty Head V nickel was produced from 1883 to 1913, with the five unauthorized coins being struck by an unknown person in 1913 (which are extremely valuable coins today).

The obverse of the coin featured a head of Liberty, surrounded by 13 stars representing the thirteen original colonies. The reverse of the nickel portrayed a wreath of cotton, corn, and wheat encircling the Roman numeral “V” for five, representing the denomination of the coin.

Originally the nickel did not have the word “cents” anywhere on it as it had not been deemed necessary. But not long after the coins entered circulation, some fraudsters realized that if they gold-plated the coins, they would pass for the gold $5 coins that were circulating at the time.

One account of fraudulent $5 coins claims that a man would buy something at a store for .05 cents and the clerk would give him change for $5.00, which the man accepted as a “gift”. Supposedly the law had nothing they could charge him with as he never bought anything worth more than the five-cent coin!

The Mint quickly worked to change the coins with the added “cents” after that!

Barber’s coins proved to be quite resilient, with many surviving today. Barber dedicated his life to studying coinage techniques and constantly working to improve technology to make better coins. He even traveled to Europe to study the Mints abroad and discuss techniques with the European Mints!

The infamous coin feud

You’ve probably heard of the feud between Saint-Gaudens and Charles Barber, (in fact we’ve got an article on it here) and we’re going to offer another perspective on that situation.

Barber was highly critical of Saint-Gaudens coin designs, and while it is certainly possible he didn’t want the competition of another designer, or even that he didn’t want his coins to stop circulating (I mean who wouldn’t want their design to be used?), In all likelihood, Saint-Gaudens coins were too high of a relief to affordably and realistically strike thousands of in a reasonable time period.

Barber eventually changed the Saint-Gaudens designs to be lower relief and the coins became incredibly popular. The Gold Double Eagle became the preferred way to hold gold for quite a while. Today, Saint-Gaudens design is featured on the American Eagle Gold series.

Charles Barber passed away in 1917, and was succeeded in office by fellow engraver George T. Morgan.

Check out some of our other articles in our Chief Engravers of the US Mint Series!

- Robert Scot

- William Kneass

- Christian Gobrecht

- James B. Longacre

- William Barber

- Charles E. Barber

- George T. Morgan

- John R. Sinnock